I'm troubleshooting why I can't receive the RGB data stream from the Framos Realsense D435e. I decided to take a step back to the Intel Realsense D435 USB, and verify the pixel format of the data stream.

The Realsense software indicates there are multiple RGB camera stream formats: YUYV, RGB8, RGBA8, etc.

Each of these streams should use a pixel format that is different from the others. The data in the communication packet should be arranged based on the pixel format. YUYV is a 16 bit per pixel format that contains the Luminance (brightness) of every pixel, and only half of the Chroma (color) data for each pixel. The rest of the Chroma data is supplied in the next pixel. So when using YUYV you need to get pixel pairs. And to make things a little more complicated, you need to convert the YUYV data to RGB data before you get the full color image.

But the goal of the test was to see what pixel formats can come from the camera. Turn out, even though there are multiple formats listed, the data in the packet is still only YUYV. Selecting RGBA8 should require more bytes per pixel, and they should be in a different pixel format, but the data packets all look the same as YUYV.

I discovered this using Wireshark's USBPcap feature. The length of the image frame packets did not change when a different stream was selected.

WireShark reports that the image data packet is 115475 bytes long. I exported the data by right clicking the hex and selecting "Copy as Escaped string", then pasting into notepad.

The actual image data starts at 0x0113 or 275 bytes into the data packet.

There are 27 bytes of USB packet data, followed by 248 bytes of image header data. I did not find a way of deciphering this image data header. I'm sure it's in a standard out there somewhere, but ain't nobody got time for that. I just calculated the number of bytes that I should get based on 320 x 180 pixels, and 2 bytes per pixel (115200 bytes) So 115475 - 115200 = 275 should be the start. And it is!

The YUV format is YUYV 4:2:2 (also this might be called YUY2).

A Microsoft developer doc describes the byte array as:

Y0U0 Y1V0 Y2U1 Y3V1 ... where there is a Y byte for every pixel, and a 'U' (Chroma blue or Cb) byte for the first (odd) pixels, followed by a 'V' (Chroma red or Cr) byte for the second (even) pixels.

To convert YUV to RGB the YUV4:2:2 is converted to YUV4:4:4 first. That just means you need Y U and V bytes for every pixel. If a pixel is missing V, just copy the V from the next even number pixel. If it is missing a U, just copy the U value from the previous pixel.

Then do some math, maybe with floating point numbers like this:

Make new variables C D & E

C = Y - 16

D = U - 128

E = V - 128

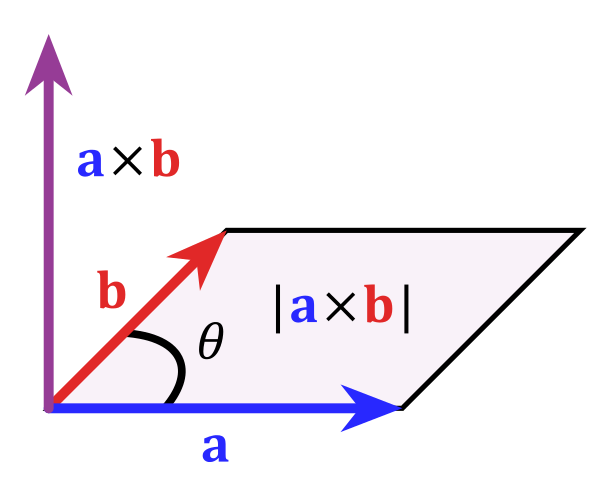

the formulas to convert YUV to RGB is:

R = clip( round( 1.164383 * C + 1.596027 * E ) )

G = clip( round( 1.164383 * C - (0.391762 * D) - (0.812968 * E) ) )

B = clip( round( 1.164383 * C + 2.017232 * D ) )

*Clip just means limit the result back to a value from 0 to 255. You can cast to an unsigned 8bit number to do this.

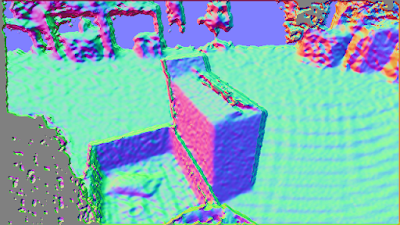

And here is the result in all it's amazing techno color:

What's up with the green box? Well just ignore that. Wire shark only captures 65535 bytes per packet.

Here are the intermediate steps:

Get the Luma Y and Chroma Cb Cr channels for all pixels:

|

| Luma |

|

| Chroma Cb |

|

| Chroma Cr |

Using the algorithm above, convert the pixels to R G B channels.

|

| R |

|

| G |

|

| B |

.svg/480px-Sphere_(parameters_r%2C_d).svg.png)